Here's what's happened in illustrations 1-8:

We know that a Romeo the wolf enjoys roaming the forest, perching majestically on rocks, and breakfasting on small, furry animals. We know that a young girl and her dog live in the area and enjoy recreating on forest trails.

We've been here before. Remember Red Riding Hood? Peter? A trio of pigs?

The suspense behind pages 9-17 rests on layer after layer of cautionary folklore about wolves. If wolves are at large, and if one owns a brick house, one stays inside and stops up one's chimney. Those brazen enough to hazard the woods alone might find themselves and their grandparents being freed from a canine esophagus by the business end of a woodsman's axe. And that's in the happy version of the story. Those old fairy tales didn't pull any punches.

I can still feel those anti-wolf instincts when I hear even the cheerful part of Tchaikovsky's theme to Peter and the Wolf.

But seasons change--stories, like layers of icy permafrost, melt and shift around. In 1906, the woods lit up. Gold prospectors carried dynamite into the Alaskan forest, and Jack London wrote White Fang, a novel about a semi-domesticated wolf/dog mix. The wolf part of White Fang was still feral, but he had an ungroomed charm, much like his Disney costar Ethan Hawke. The wolves and forest were beginning to win our sympathies as we began to dominate the woods.

Cut to 2012. In Alaska, wolf populations are modeled statistically, and extensive lawsuits still contest whether we need to reduce wolf numbers by shooting wolves from planes and helicopters. So much for primeval mystique--Peter has a gun and GPS. The dark place that we used to fear is at the mercy of an equation that humans control. We have pierced that dense forest that has frightened us since Disney was a smear of charcoal on a cave wall, and somehow that reality is a bit scarier. Agoraphobia sets in.

Before Avatar or Fern Gully, there was Bambi. Bambi's mother called the forest the "thicket," a word that sounds like a small, helpless animal ducking for cover in the underbrush. And that's what it means. The thicket is a place of shelter and safety that should not be departed hastily. As much as I fear the music behind Peter and the Wolf, Tchaikovsky's darkest chords will never chill me more than the shrill horns, followed by the wide open quiet behind Bambi's mother's prophetic warning.

"You must never rush out on the meadow. . . out there, we are unprotected."

Unprotected from what?

Unprotected from what?

We are parked here on the fringe between the meadow and the thicket. That's where pages 9-17 take us. Is it safe here for either of us? For wolf, or dog, or human?

There's really only one way to find out. That way is to walk in circles with the wolf a few times and sniff its hindquarters. After thousands of years of evolution, technology, and reactive storytelling, at least some things really haven't changed that much.

DESIGN NOTE

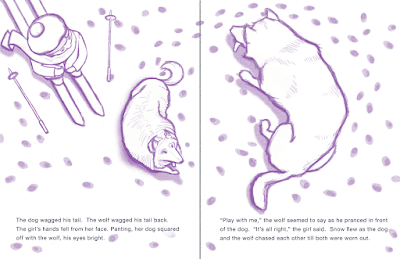

I'm drawing in color here because I might want to change my lines to off-black before printing, and hue-shifting is easier if my lines have some color in them from the start. Also, it's more fun this way.

I'm drawing in color here because I might want to change my lines to off-black before printing, and hue-shifting is easier if my lines have some color in them from the start. Also, it's more fun this way.

Comments

Post a Comment